GARY N. WILSON

1 history and development of federalism

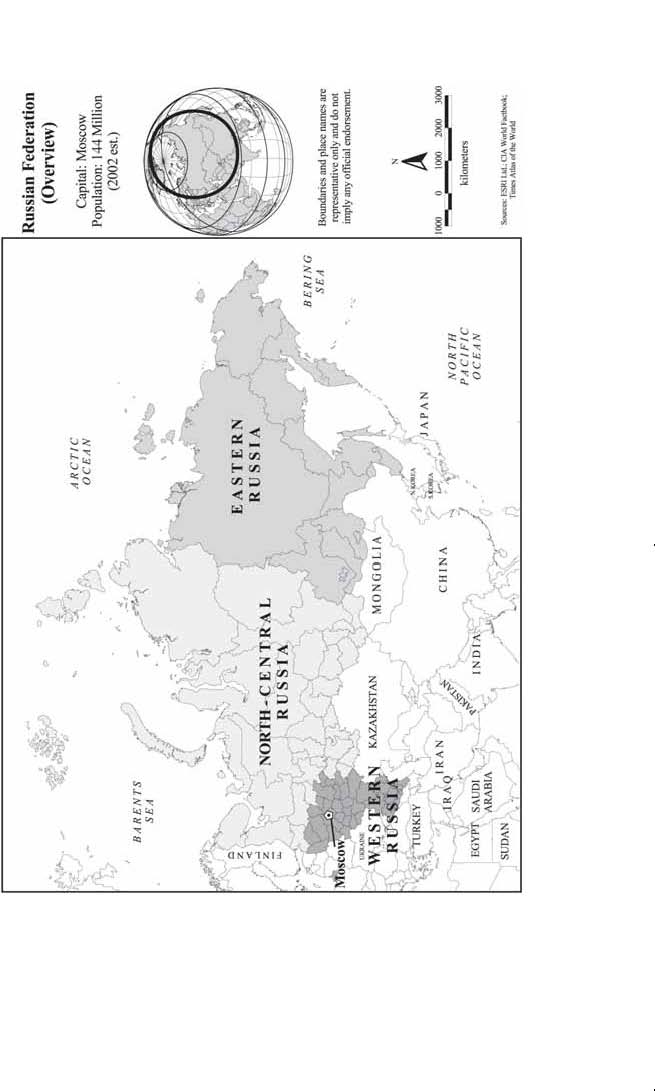

The Russian Federation is the world’s largest federal state (17,075,000 km2). A vast country, spanning two continents and 11 time zones, it is home to approximately 145 million people. With a population of more than 8 million, Russia’s capital, Moscow, is one of the largest cities in Europe. Although ethnic Russians constitute a majority (80%) of the country’s population and Russian is the official state language, the Russian Federation contains over 100 distinct nationalities and ethnic groups. A number of these national groups are territorially based and have the political authority to preserve and promote their respective cultures and languages.

Russia has a rich and storied history. The origins of modern Russia, however, can be traced to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries when the various principalities of European Russia came under the domination of Moscow. In the centuries to follow, the Russian tsars (kings) spearheaded the eastern and southern expansion of the Russian Empire. The development of the modern Russian state structure (bureaucracy and military) began in the late seventeenth century, during the reign of Peter the Great, and continued under subsequent members of the Romanov dynasty. By the early nineteenth century, Russia was considered a major European power and one of several empires that dominated the global political scene.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, however, Russia experienced a series of radical political and societal transformations, and military setbacks. The cumulative pressures of modernization, industrialization and urbanization, coupled with popular demands for a relaxation of the autocratic system of government and the harsh conditions of World War I would ultimately lead to the overthrow of the tsarist regime and the creation of the Soviet Union.

Under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik (majority) faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party seized power in October 1917 and proceeded to consolidate its hold over the vast territory that comprised the former Russian Empire. Following the civil war of 1917–21, Bolshevik-inspired communist factions came to power in many of the regions of the former empire and joined to form the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (ussr).

The Soviet Union’s federal status was theoretically enshrined in the 1936 constitution. In practice, however, the federal model that existed during the Soviet period was a façade that veiled a highly centralized political and economic system. Although the various republics that comprised the federation had limited autonomy over cultural and some administrative matters, the overwhelming dominance of centralized structures such as the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (cpsu) and the systems of economic planning and administration effectively nullified the country’s federal character.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, nationalist tensions, emanating from the constituent members of the federation (the Union-Republics), initiated the downfall and disintegration of the Soviet Union. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost (openness) encouraged nationalist groups and politicians in the republics to press for greater autonomy and even independence from Moscow. At the same time, the rigid, centralized institutional apparatus began to give way under the weight of reforms (perestroika/reconstruction) that exposed the structural weaknesses of the Soviet regime. The Soviet Union eventually disintegrated in the wake of a failed hard-line coup attempt against Gorbachev in August of 1991.

Russia’s first post-Soviet President, Boris Yeltsin, was actually elected President of the Soviet Union’s largest Union-Republic, the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (rsfsr), in June 1991, prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union. Yeltsin was instrumental in opposing the above-mentioned coup attempt and became President of the independent Russian Federation on 25 December 1991 when the Soviet Union ceased to exist.

Boris Yeltsin dominated Russian political life throughout the 1990s. In 1993, he successfully engineered the passage of a constitution which gave the President wide-ranging powers. Despite periodic setbacks, most of which were related to Yeltsin’s declining health, and a series of short-lived Prime Ministers, he remained in power until 31 December 1999, when he voluntarily stepped down as President. This set in motion a new phase in the country’s post-Soviet political history. Vladimir Putin, a relatively unknown former member of the security services from St. Petersburg, became Acting President. Putin, who had been appointed Prime Minister by Yeltsin in 1999, was elected President in March 2000.

Over the past decade, one of the most pressing issues facing the Russian Federation’s democratically elected leaders has been the task of constructing a stable and integrated federal state. In many respects, the choice of a federal system of government was the only acceptable option at the outset of the transition. The Russian Federation inherited the complicated regional structure of former rsfsr. In the late 1980s, many of the rsfsr’s regions had become involved in the broader struggle for autonomy taking place at the Union-Republic level and both Gorbachev and Yeltsin offered concessions of autonomy to the rsfsr’s diverse regions in an attempt to bolster their own respective authority. In the early post-Soviet period, many feared that the Russian Federation would suffer the same fate as its Soviet predecessor. The territorial integrity of the Russian Federation, however, was preserved when all but two of the former constituent units of the rsfsr signed the Federation Treaty in March 1992. Only the republics of Tatarstan and Chechnya refused to sign this treaty. Tatarstan later negotiated its formal entry into the Russian Federation on the basis of a bilateral treaty in 1994. The Chechen government, on the other hand, has never fully recognized its incorporation into the Russian Federation and remains a painful thorn in Moscow’s side.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation has undergone a period of intense political, economic and social transition. Steps have been taken to reform the economy and create a viable civil society and party system, but the legacies of 75 years of communist rule and the negative impact of transition on society remain major impediments to the construction of viable democratic and market institutions. In many respects, the uncontrolled decentralization of power to the federal units that occurred during the 1990s contributed to the political and economic confusion facing the country by weakening the federal government and undermining its ability to coordinate the national reform program.

The Soviet Union played a major role in world politics for much of the twentieth century. After the forced agricultural collectivization and industrialization of the country in the 1930s and its major role in the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II – events that exacted an enormous toll on the country’s population – the Soviet Union became a feared and respected global superpower, and was granted one of five permanent seats on the United Nations Security Council (which Russia retains). In recent years, however, Russia’s status as an international power has declined considerably.

According to the latest United Nations’ Human Development Index (2003), the Russian Federation ranks 63rd out of 193 countries and territories surveyed. Its gdp per capita is us$7,900 and life expectancy (at birth) is 66.6 years. Despite the recent setbacks, Russia has tremendous potential, especially in terms of its highly literate and educated population and its enormous natural resource wealth (oil, gas, minerals, precious metals and timber).

2 constitutional provisions relating to federalism

The political system outlined in the Russian constitution (adopted on 12 December 1993 in a national referendum) is a unique hybrid of a presidential and parliamentary republic. The President appoints the Cabinet ministers, including the Prime Minister (formally referred to as the Chairman of the Government), but these ministers must also retain the confidence of the Parliament to govern. Cabinet ministers, however, do not have to be elected members of the legislature, as in the Westminster parliamentary model.

As the head of state, the President plays a very important role in the exercise of power. He or she has the authority to issue presidential decrees. These decrees have the force of law, but may not violate existing laws and can be superseded by laws passed by the Parliament. Under certain conditions, the President can also dissolve Parliament.

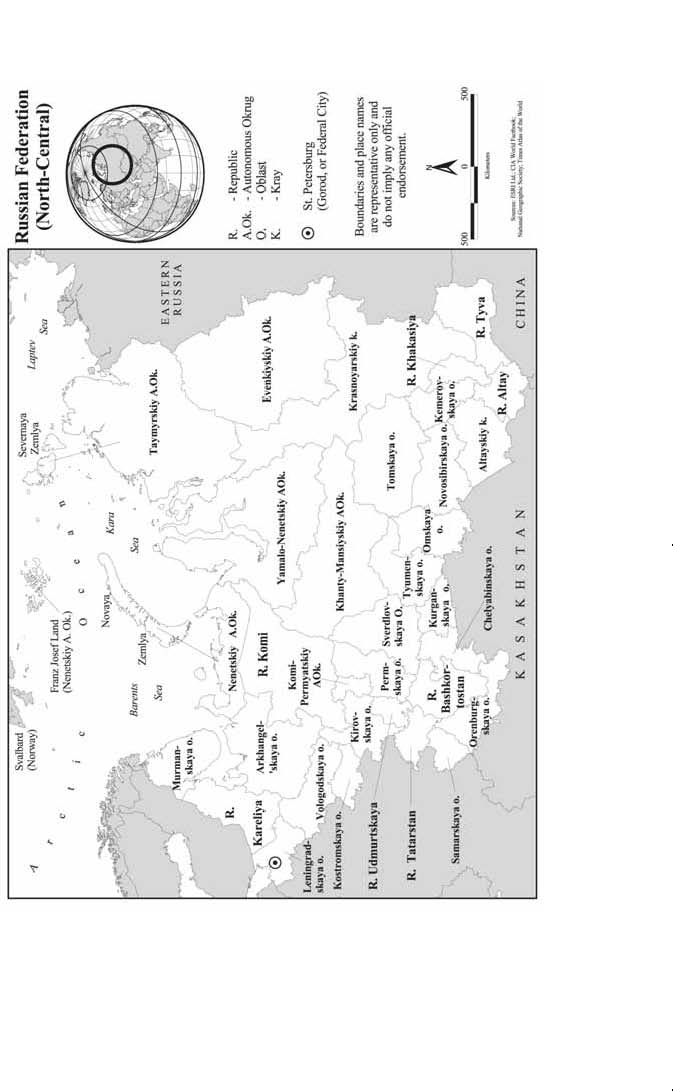

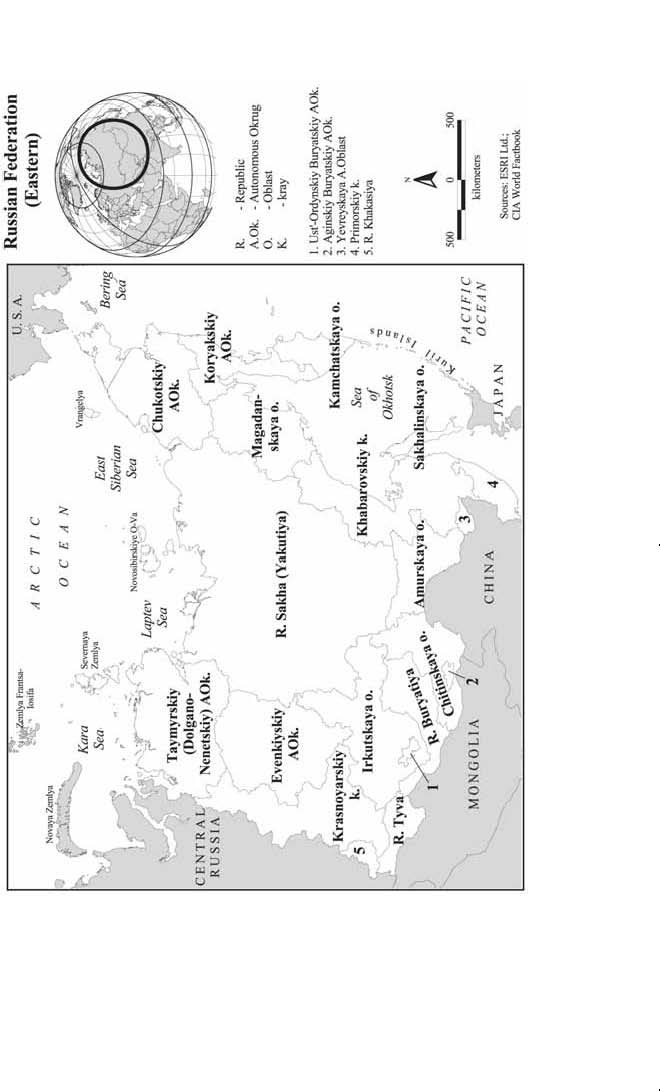

The organization of the federation is outlined in Chapter 3, Articles 65 to 79 of the constitution and in earlier articles on the principles of the constitutional system (Chapter 1). The federation is comprised of 89 constituent units: 21 republics, 49 oblasts (regions), six krais (territories), 10 autonomous okrugs (districts), one autonomous oblast and 2 federal cities (Moscow and St. Petersburg (Article 65)). The republics are situated at the top of the federal hierarchy. Their status is based on the fact that they contain significant non-Russian ethnic populations (Tatars in Tatarstan, Bashkirs in Bashkortostan, etc.). Oblasts and krais are non-ethnically-based regions and generally have less autonomy than republics. Autonomous okrugs have a rather ambiguous position within the federal hierarchy. These ethnically-based districts are the homelands of Russia’s indigenous aboriginal populations. Constitutionally speaking, they are considered both separate members of the federation and parts of the oblasts and krais in which they are located; a situation that has led to numerous jurisdictional disputes over the past decade.

These constituent units are represented at the federal level of government in the Federation Council, the upper chamber of Russia’s bicameral Parliament. Each constituent unit has two representatives in the Federation Council. Territorial representation also exists in the State Duma, the lower chamber of the Parliament. Half of the 450 Duma deputies are elected from constituencies across Russia, while the other half are elected on the basis of proportional representation.

The constitution contains both symmetric and asymmetric federal features. Article 5(1) of the constitution states that all the constituent units are equal members of the federation. Similarly, Article 5(4) says that all the constituent units are equal in their relations with federal bodies of state authority. Article 5(2), on the other hand, states that only republics shall have their own constitutions and laws. The other constituent units are entitled to their own statutes and laws. Article 68(2) gives the republics the right to establish their own state languages, in addition to Russian (usually the language of the titular, non-Russian nationality).

It is important to note that there are a number of non-constitutional treaties and agreements that strengthen the asymmetrical character of the federal framework. The above-mentioned Federation Treaty, for example, is actually a series of three different treaties between the federal government and the republics, the oblasts and krais, and the autonomous okrugs, oblasts and federal cities. The republican version, for example, gives the republics greater autonomy than the other regions. During the 1990s, many individual constituent units signed special bilateral treaties with the federal government. In many cases these treaties provided the members in question with more autonomy in relation to the federal government than members that have not signed bilateral treaties. The constitutional status of the bilateral treaties, however, is still unclear. Although Article 11(3) of the constitution does state that the demarcation of authority between the Russian Federation and the constituent units can be realized through the constitution and other agreements on the demarcation of subjects of jurisdiction and authority, the provisions of the bilateral treaties (and the Federation Treaty, for that matter) are not included in the constitution. As such, the federal government has consistently viewed these treaties as sub-constitutional documents.

According to Article 15 of the constitution, laws passed by the constituent units are not allowed to contravene the federal constitution. While such a provision may exist in theory, one of the most controversial disputes of the post-Soviet period has been the “war of laws” between the federal government and the constituent members. In 2000, for example, the Russian Ministry of Justice revealed that upwards of 50,000 regional legislative acts did not comply with the federal constitution or federal laws.

The division of powers between the federal government and the constituent units is outlined in Articles 71 to 73 of the constitution. Article 71 lists the federal areas of jurisdiction. These include such matters as the regulation and protection of human rights and freedoms, the financial and banking system, federal energy systems, foreign policy, international relations and external economic relations, defence and security, and the organization of the court system. Areas of concurrent or joint jurisdiction between the federal government and the constituent units are outlined in Section 72. Among the more important matters of concurrent jurisdiction are questions relating to the possession, use and disposal of lands, minerals, water and other natural resources, education, science and public health. Article 73 states that any areas of government not outlined in Articles 71 and 72 fall under the jurisdiction of the constituent units.

The most controversial aspect of this division of powers is the ambiguous nature of the concept of concurrent jurisdiction. As a result of frequent political stalemates at the federal level, many regions have acted unilaterally in areas of concurrent jurisdiction. Consequently, their legislation often contradicts the federal constitution or subsequently adopted federal laws. The constitution itself is very unclear about how the federal government and the constituent units are supposed to coordinate their legislative activities.

The constitution, however, does outline two particular mechanisms for resolving disputes between the federal government and the constituent units or between the constituent units. Article 85 states that the President may use reconciliatory procedures to settle such disputes. If no agreement is reached, the President may send the case to the appropriate court. The President also has the power to suspend executive acts of the constituent units if they contradict the federal constitution, federal laws, the international obligations of the Russian Federation or constitute a breach of human or civil rights and freedoms.

The 1993 constitution makes provision for a Constitutional Court. The main responsibilities of the Court are to rule on the constitutionality of the laws and other normative acts that are adopted by the legislative and executive branches of government. Another important function is to delineate and interpret the division of powers between the federal government and the constituent unit governments. The constitution states that the 19 judges that sit on the Court must be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Federation Council.

As a result of political infighting following the ratification of the constitution in December 1993, the Court was suspended until March 1995.1 Since its reinstatement, it has worked to establish its autonomy and authority in relation to the other branches of government and the constituent units. The Court has made a number of important decisions on the constitutionality of regional laws, but at times has met stiff opposition from the governments of the constituent units.

Proposals for amending the federal constitution may be submitted by a variety of institutions including the President, the Federation Council, the State Duma, the government of the Russian Federation, and the legislative bodies of the constituent units. Proposals for amending Chapters 1, 2 and 9 of the federal constitution (Principles of the Constitutional System, Human and Civil Rights and Freedoms, Constitutional Amendments and Revision of the Constitution) must first receive the support of three-fifths of the Federation Council and the State Duma. The proposal is then submitted to a specially convened constitutional assembly, which confirms the existing constitution or drafts a new document. The new document passes if it receives two-thirds support of the constitutional assembly or more than one-half of eligible voters in a nationwide referendum. Changes to Chapters 3 to 8 of the federal constitution, on the other hand, require the approval of at least two-thirds of the constituent units.

Russia’s system of fiscal federalism is a complicated web of established and negotiated taxes, revenue sources and regional assistance funds. Since 1991 considerable revenues and expenditures have been transferred from the federal government to the constituent units, and at present, their share of tax revenues is about 50 per cent of total revenues. In theory, the units are supposed to remit a negotiated portion of their tax revenues to the federal government. Value added (vat) and corporate profit taxes and excises are shared between the federal government and the constituent units at negotiated rates, while personal

1 A Russian Constitutional Court was initially established in July 1991, prior

to the breakup of the Soviet Union. At that time, the Soviet Parliament –

the Congress of People’s Deputies – elected the Court’s 15 judges. In the

period between 1991 and 1993, the Court was involved in a number of po

litical disputes, culminating in the conflict between President Yeltsin and

the Russian Parliament in 1993. After proposing a resolution to the crisis

that was accepted by both sides, the head of the Court, Valerii Zorkin, sided

with the parliamentary cause and later condemned Yeltsin’s decision to sus

pend the Parliament. Yeltsin responded by suspending the Court until a

new constitution could be ratified.

income tax is given entirely to the constituent units. The State Tax Service, which is responsible for collecting taxes, has been administratively subordinated to the federal government since 1991. In reality, however, tax collectors are often loyal to and dependent on the administrations of the constituent units.

Of the 89 federal units that comprise the Russian Federation, less than 10 can be classified as donor or “have” regions (meaning they remit more revenues to the federal government than they receive in subsidies). The importance of negotiation as a tool for determining revenue flows means that politics plays a critical role in the fiscal system. In the past, the federal government has used fiscal federalism to shore up support for the regime or provide incentives for accepting political deals. Often, politically powerful constituent units pay less tax than they are supposed to, while the weaker units bear the brunt of the taxation burden. More importantly, the financial difficulties experienced by the Russian state during the turbulent economic transition period have meant that many constituent units have not received the fiscal subsidies to which they are entitled.

3 recent political dynamics

Buoyed by high world resource prices, Russia’s financial situation has improved in recent years. A tremendous amount of work needs to be done, however, before Russia completes its transition to a market economy. Most importantly, the government must put in place a stable and comprehensive legal environment for business activities and foreign investment. The economy also needs to be further diversified in order to decrease Russia’s reliance on volatile natural resource markets. Without such reforms, the economy will struggle to combat corruption, compete internationally and grow over the long term.

In the post-Yeltsin period – i.e., the Putin period – Russia’s fledgling democratic system has continued to experience significant growing pains. Despite the fact that the country’s democratic institutional framework has a constitutional foundation and elections at all levels of government have been held on a regular basis, Russia’s civil society remains weak and electoral contests, in particular those at the regional level, have been tainted by irregularities. The mass media have become increasingly controlled by the state, a process that has accelerated under President Putin. Independent journalists and media owners who are critical of the government and its policies have faced prosecution, persecution and harassment.

Since coming to power, Putin has embarked on an ambitious series of reforms to Russia’s federal structure. His primary goals are to strengthen the authority of the federal government in relation to the constituent units and harmonize federal and regional legislation. First, he authorized the creation of seven federal okrugy (districts) – Central, North Caucasus, Northwest, Volga, Urals, Siberia and Far East. Each district encompasses approximately 10 to 12 geographically concentrated constituent units. The districts are headed by federally-appointed presidential representatives who are primarily responsible for overseeing the activities of the constituent units and making sure that regional laws comply with their federal counterparts and the federal constitution. Although it is fair to say that the presidential representatives are endowed with considerable authority, it should be noted that in practice this authority is checked by other actors within the political system, including federal ministries and agencies, and the regional governments themselves. This reality has complicated the work of the presidential representatives.

The second major federal reform initiated by the Putin government has involved changes to the composition of the Federation Council. As noted above, in the past each member of the federation had two representatives on the Federation Council: the respective heads of the regional legislative and executive branches. Now, however, the constituent units are required to have “full-time” Senators, one appointed by the head of the executive branch and the other elected by the legislature.2

This arrangement was supposed to make the Federation Council a more efficient and effective institution. Observers have noted, however, that the opposite may be true because the representatives face the constant threat of being recalled by their regional sponsors. Perhaps one of the most striking impacts of this particular reform has been the dramatic increase in the number of Moscow-based officials and members of the business elite holding representative positions within the upper chamber. Many regions have appointed these individuals as their representatives in the hope that they can use their influence to leverage federal aid and support. While this may be seen as beneficial to the regions, the fact that many Federation Council representatives have no direct personal links with the regions they represent in part undermines the federal nature of the upper chamber.

In order to placate the regional heads who no longer have a seat in the federal Parliament as a result of the changes to the Federation Council, Putin has created two new federal consultative bodies: the State Council and its Presidium. The State Council includes all the

2 Federal law “On the order of formation of the Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation.”

Governors and Presidents of the constituent units and meets quarterly at the request of the Russian President to discuss particular issues. The Presidium is comprised of seven members of the State Council (determined on a rotating basis) and meets on a monthly basis. These new bodies give the regional leaders an opportunity to express their opinions on major initiatives undertaken by the federal government.

The recent institutional reform of the Russian federation has been accompanied by legislative measures designed to strengthen the power of the federal government at the expense of the regions. Amendments to legislation passed at the end of 1999 gave the President and federal bodies the power to dismiss regional Governors and legislatures, in the event that they violate federal legislation.3 As was the case with the changes to the Federation Council and the creation of the State Council, Putin has attempted to balance this legislative reform by giving regional Governors the right to dismiss lower level administrative heads. Putin also gave his support to legislation that allowed regional Governors and Presidents to seek third and fourth terms in office, despite the fact that this violated some regional charters and republican constitutions.

Much of the work of restoring the authority of the federal government has been carried out under the auspices of a special commission headed by Dmitrii Kozak, the Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration. The Kozak Commission has been charged with the task of overseeing the process of legislative harmonization, as well as reforms dealing with local self-government.

In addition to reforms to federal level institutions and attempts at restoring the authority of the federal government in the regions, Putin has also taken steps to encourage a reduction in the number of regions by signing a law on voluntary regional consolidation.4 The law sets out a process for completing the mergers, which includes referenda in all the affected regions, approval by the President, the State Duma and Federation Council, and an amendment to the constitution. Regions containing autonomous okrugs are expected to be the first to undergo the merger process.

3 Although the amendments to the law “On the general principles of the or

ganization of the legislative and executive organs of state power of the sub

jects of the Russian Federation” do give the President and other federal

bodies the power to dismiss regional Governors and legislatures, it should

be noted that the process for carrying out such a change is complicated.

4 Federal law “On the order of adopting and establishing new federation

subjects.”

One of the more problematic aspects of Russian federalism is the continuing conflict in the Republic of Chechnya. In recent months the conflict has extended beyond the boundaries of Chechnya with a spate of suicide bombings and attacks in major cities, including Moscow, attributed to Chechens. Like Yeltsin, Putin has sought to resolve the conflict through military means, thus far without success. As a result, Chechnya remains a persistent and bloody sore on the Russian federal system with no clear resolution in sight.

One of the greatest challenges facing Russia in the future is the task of redefining its position with its regional neighbours and the West. Through organizations such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (cis) – a confederation of independent states that were formerly members of the Soviet Union – Russia has encouraged closer cooperation among the countries of the area. The political union with Belarus, and Russia’s involvement in the Caspian region and Central Asia suggest that it will continue to play a dominant role as a regional power.

Russia’s position on the world stage, however, has waned since the Soviet period. Its relationship with the West and, in particular the United States, is fraught with ambiguity. Russia depends on Western economic assistance for its financial well-being and is seeking to integrate itself into the Western financial system through organizations such as the Group of Eight (g-8) and the World Trade Organization (wto). (It is not yet a member of the wto.) At the same time, Russia wants to assert its political autonomy and authority in an increasingly monopolar world and has strongly opposed such Western initiatives as the 1999 nato bombing of Yugoslavia and nato’s expansion into Eastern Europe. And, although supportive of the American-led “war on terror” that followed the events of 11 September 2001, Russia sided with France, Germany and other opponents of the US war in Iraq in 2003.

4 sources for further information

Alexseev, Mikhail (ed.), Centre-Periphery Conflict in Post-Soviet Russia: A

Federation Imperiled, New York, ny: St. Martin’s Press, 1999. Hanson, Philip and Michael Bradshaw (eds), Regional Economic Change

in Russia, Cheltenham, uk: Edward Elgar, 2000. Hyde, Matthew, “Putin’s Federal Reforms and their Implications for Pres

idential Power in Russia,” Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 53 (2001), pp. 719–

743. Kahn, Jeffrey, Federalism, Democratization and the Rule of Law in Russia, New York, ny: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Kelly, Donald R., Politics in Russia and the Successor States, Fort Worth, tx: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1999.

Nicholson, Martin, Towards a Russia of the Regions, London: International Institute for Strategic Studies – Adelphi Paper, 1999. Remington, Thomas F., Politics in Russia, New York, ny: Longman, 2002.

Ross, C., “Putin’s Federal Reforms and the Consolidation of Federalism in Russia: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back!” Communist and Post-Communist Studies, Vol. 36 (2003), pp. 29–47.

Westlung, Hans, Alexander Granberg and Folke Snickars, Regional Development in Russia: Past Policies and Future Prospects, Cheltenham, uk: Edward Elgar, 2000.

http://www.gov.ru http://www.government.gov.ru http://www.regions.ru http://www.iews.org http://www.finruscc.fi/en/a/3fb/k3fb.htm

Table I Political and Geographic Indicators

| Capital city | Moscow |

| Number and type of constituent units | 89 constituent units: 21 Republics: Adygeya, Altai, Bashkortostan, Buryatiya, Chechnya, Chuvash, Daghestan, Ingushetia, Kabardino-Balkarian, Kalmykia, Karachayevo-Cherkesian, Kareliya, Khakassia, Komi, Mariy El, Mordovia, Sakha (Yakutia), North Ossetia-Alania, Tatarstan, Tyva, Udmurtian 49 Regions (oblasts): Amur, Arkhangelsk, Astrakhan, Belgorod, Bryansk, Chelyabinsk, Chita, Irkutsk, Ivanovo, Kaliningrad, Kaluga, Kamchatka, Kemerovo, Kirov, Kostroma, Krugan, Kursk, Leningrad, Lipetsk, Magadan, Moscow, Murmansk, Nizhni, Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Orenburg, Oryol, Penza, Perm, Pskov, Rostov, Ryazan, Sakhalin, Samara, Saratov, Smolensk, Sverdlovsk, Tambov, Tomsk, Tula, Tver, Tyumen, Ulyanovsk, Vladimir, Volgograd, Vologda, Voronezh, Yaroslavl 6 Territories (krais): Altai, Khabarovsk, Krasnodar, Krasnoyarsk, Primorie, Stavropol 10 Autonomous Areas (okrugs): Aginsk Buryat, Chukotka, Evenki, Khanty-Mansi, Komi-Permyak, Koryak, Nenets, Taimyr (Dolgano-Nenets), Ust-Ordyn Buryat, Yamalo-Nenets |

| 1 Jewish Autonomous Region (oblast): Yevreyskaya 2 Cities of Federal Significance: Moscow, St. Petersburg | |

| Official language(s) | Russian |

| Area | 17 075 200 km² |

Area – largest constituent unit Sakha (Yakutia) – 3 103 200 km2

Area – smallest constituent St. Petersburg – 600 km2 unit

Total population 144 071 000 (2002)

Population by constituent unit (% of total population)1

Moscow (city) 7.1%, Moscow (oblast) 4.6%, Krasnodar 3.5%, St. Petersburg 3.2%, Sverdlovsk 3.1%, Rostov 3.0%, Bashkortostan 2.8%, Tatarstan 2.6%, Chelyabinsk 2.5%, Nizhny Novgorod 2.4%, Samara 2.2%, Tyumen 2.2%, Krasnoyarsk 2.0%, Kemerovo 2.0%, Stavropol 1.9%, Perm 1.9%, Volgograd 1.9%, Saratov 1.8%, Dagestan 1.8%, Irkutsk 1.8%, Novosibirsk 1.8%, Altai (territory) 1.8%, Voronezh 1.6%, Orenburg 1.5%, Omsk 1.4%, Primorsky 1.4%, Udmurtia 1.1%, Tula 1.1%, Yaroslavl 1.1%, Leningrad 1.1%, Penza 1.0%, Vladimir 1.0%, Belgorod 1.0%, Khabarovsk 1.0%, Tver 1.0%, Kirov 1.0%, Khanty-Mansi 1.0%, Chuvash 0.9%, Arkhangelsk 0.9%, Ulyanovsk 0.9%, Vologda 0.9%, Bryansk 0.9%, Chita 0.8%, Ryazan 0.8%, Kursk 0.8%, Lipetsk 0.8%, Ivanovo 0.8%, Tambov 0.8%, Chechen 0.7%, Tomsk 0.7%, Kurgan 0.7%, Komi 0.7%, Buryatia 0.7%,

Table I (continued)

Smolensk 0.7%, Astrakhan 0.7%, Kaluga 0.7%, Orel 0.6%, Sakha 0.6%, Mordovia 0.6%, Amur 0.6%, Kaliningrad 0.6%, Murmansk 0.6%, Kabardian-Balkar 0.6%, Kostroma 0.5%, Mariy El 0.5%, North Ossetia-Alania 0.5%, Novgorod 0.5%, Pskov 0.5%, Karelia 0.5%, Sakhalin 0.4%, Khakassia 0.4%, Karachaev-Circassian 0.3%, Adygeya 0.3%, Yamalo-Nenetz 0.3%, Ingushetia 0.3%, Kamchatka 0.2%, Kalmykia 0.2%, Tuva 0.2%, Magadan 0.1%, Jewish Autonomous Oblast 0.1%, Komi-Permyatsky 0.1%, Altai (oblast) 0.1%, Ust-Ordyn Buryat 0.09%, Aginski Buryat 0.05%, Chukchi, 0.04%, Nenets 0.02%, Taimyr 0.02%, Koryak 0.02, Evenki 0.01%

Political system – federal Federal Republic

| Head of state – federal | President Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (since 26 March 2000). Directly elected to serve a 4-year term. Next election to be held 14 March 2004. |

| Head of government – federal | Prime Minister (Chairman of the Government) Mikhail Mikhaylovich Kasyanov (since 7 May 2000). President appoints the Prime Minister and Cabinet, subject to the approval of Parliament. |

| Government structure – federal | Bicameral: Federal Assembly (Federalnoye Sobranie): Upper House – Federation Council (Sovet Federatsii), 178 seats. The term of members depends on the republic or the region that they represent. |

| Lower House – State Duma (Gosudarstvennaya Duma), 450 seats. 225 members are elected by proportional representation from party lists winning at least 5% of the vote, and 225 members are elected from single-member constituencies. Members are elected to serve 4-year terms. Election last held 7 December 2003. | |

| Number of representatives in lower house of federal government of most populated constituent unit | Moscow (city) – 15 |

| Number of representatives in lower house of federal government for least populated constituent unit | Evenki – 2 |

| Distribution of representation in upper house of federal government | Each of the 89 constituent units has 2 representatives in the Federation Council: 1 elected by the legislature and 1 appointed by the executive of the state authority. |

Table I (continued)

| Distribution of powers | The constitution gives 18 exclusive powers to the feder |

| ation including foreign policy, defence, energy, citizen | |

| ship, commerce, customs, finance, nationwide public | |

| services, justice and the design of economic, social and | |

| cultural policies. There are 11 concurrent powers: pub | |

| lic order, education, culture, science and technology, | |

| health, social security, land and property, natural | |

| resources, environment, labour and family law and the | |

| oversight of local governments (including the princi | |

| ples of taxation by the republics). The coordination of | |

| the international relations and external trade of the | |

| republics is effected jointly by the federal government | |

| and the republics. The republics have the status of sub | |

| jects in international relations and external trade. In | |

| the event of conflict, federal law will prevail. | |

| Residual powers | Residual powers belong to the constituent units. |

| Constitutional court (highest | Constitutional Court. 19 judges appointed for life by |

| court dealing with constitu | the President and confirmed by the Federation Coun |

| tional matters) | cil. |

Political system of constituent units

Unicameral: Legislature Duma or Assembly. Constituent units have their own executive branches and legislatures (elected for 2-5 year terms). The republics have a President or Prime Minister (or both) elected by popular vote and a regional council or legislature. The chief executives of the lower jurisdictions (called Governors or administrative heads) are appointed by the President. The President can appoint and remove the chief executives of the jurisdictions (including the territories, oblasts, autonomous regions, and the autonomous oblast) who are responsible for overseeing the implementation of presidential policies at the local level.

Head of government – constit-Governor, President or Chairman of the Government uent units

Table II Economic and Social Indicators

| gdp | us$1.14 trillion at ppp (2002) |

| gdp per capita | us$7 926 at ppp (2002) |

| Mechanisms for taxation | us$165.4 billion (September 2003) |

| National debt (external) | n/a |

| National unemployment rate | 8.5% (June 2003) |

| Constituent unit with highest unemployment rate | Ingush Republic – 52% (October 1997) |

| Constituent unit with lowest unemployment rate | Evenki – 3.5% (October 1997) |

| Adult literacy rate | 99.6% (2001)2 |

| National expenditures on education as a % of gdp | 4.4 % (2000) |

| Life expectancy in years | 66.6 (2001) |

| Federal government revenues – from taxes and related sources | us$54.2 billion (2002) |

| Constituent units revenues – from taxes and related sources | us$52.5 billion (2002) |

| Federal transfers to constituent units | us$12.4 billion (2002) |

| Equalization mechanisms | Formula-driven equalization transfers from the “Fund for the Financial Support of Regions” |

Sources

Central Bank of the Russian Federation, “External Debt of the Russian Federation as of January-June 2003,” web site: http://www.cbr.ru/eng/statistics/credit_statistics/ print.asp?file=debt_e.htm

Central Bank of the Russian Federation, “Russia: Economic and Financial Situation.” April 2003, web site: http://www.cbr.ru/eng/today/publications_reports/ Rus0403e.pdf

Dabla-Norris, Era et. al. April 5-7, 2000. “Fiscal Decentralization in Russia: Economic Performance and Reform Issues.” Available from International Monetary Fund web site: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/seminar/2000/invest/pdf/norris.pdf

Elections Around the World, “Elections in Russia.” 2003, web site: http:// www.electionworld.org/russia.htm

International Monetary Fund, “imf Country Report: Russian Federation – Statistical Appendix.” May 2003, web site: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2003/ cr03145.pdf

International Monetary Fund, “Russian Federation: Recent Economic Developments.” September 1999. imf Staff Country Report No. 99/100, web site: http:// www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/1999/cr99100.pdf

Russia, Government of, Council of Federation, “The Constitution of the Russian Federation,” web site: http://www.council.gov.ru/gen_inf_e.htm

State Committee of the Russian Federation on Statistics, Handbook “Russia ‘2002.” 2002, web site: http://www.gks.ru/eng/bd.asp

State Committee of the Russian Federation on Statistics, “Number of de-jure (resident) population on subjects of the Russian Federation.” 2002, web site: http:// www.gks.ru/scripts/free/1c.exe?XXXX25R.1.1

United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2003: Human Development Index. 2003, web site: http://www.undp.org/hdr2003/pdf/ hdr03_HDI.pdf

World Bank, Russia Country Department, “Russian Economic Report.” August 2003, web site: http://www.worldbank.org.ru/ECA/Russia.nsf/ECADocByUnid/ 0CF40EF2E501A275C3256CD1002B7D90/$FILE/RER6-English.pdf

World Bank, “Quick Reference Tables: Data and Statistics,” web site: http:// www.worldbank.org/data/quickreference/quickref.html

World Directory of Parliamentary Libraries: Russia. Available from German Bundestag web site: http://www.bundestag.de/bic/bibliothek/library/russi.html

Notes

1 Discrepancy may exist due to rounding.

2 Age 15 and above.